Hello folks! I’m back with the third installment of Conlanging 101: How to Create a Language. In Part 1, I described how to create the sounds of your language. In Part 2, I talked about creating word roots. Check them out if you have not read them yet, for they have some essential information!

Next, if you’d like to see my method applied in action, check out my series, The Warriors of Bhrea here! Not only will you get to see the fruits of my conlanging, but you’ll get an action-packed story out of the deal as well.

So what’s next when it comes to creating a language? When you have your sounds and have put together a few roots, the next step is to structure the roots to create words and meaning.

Morphology

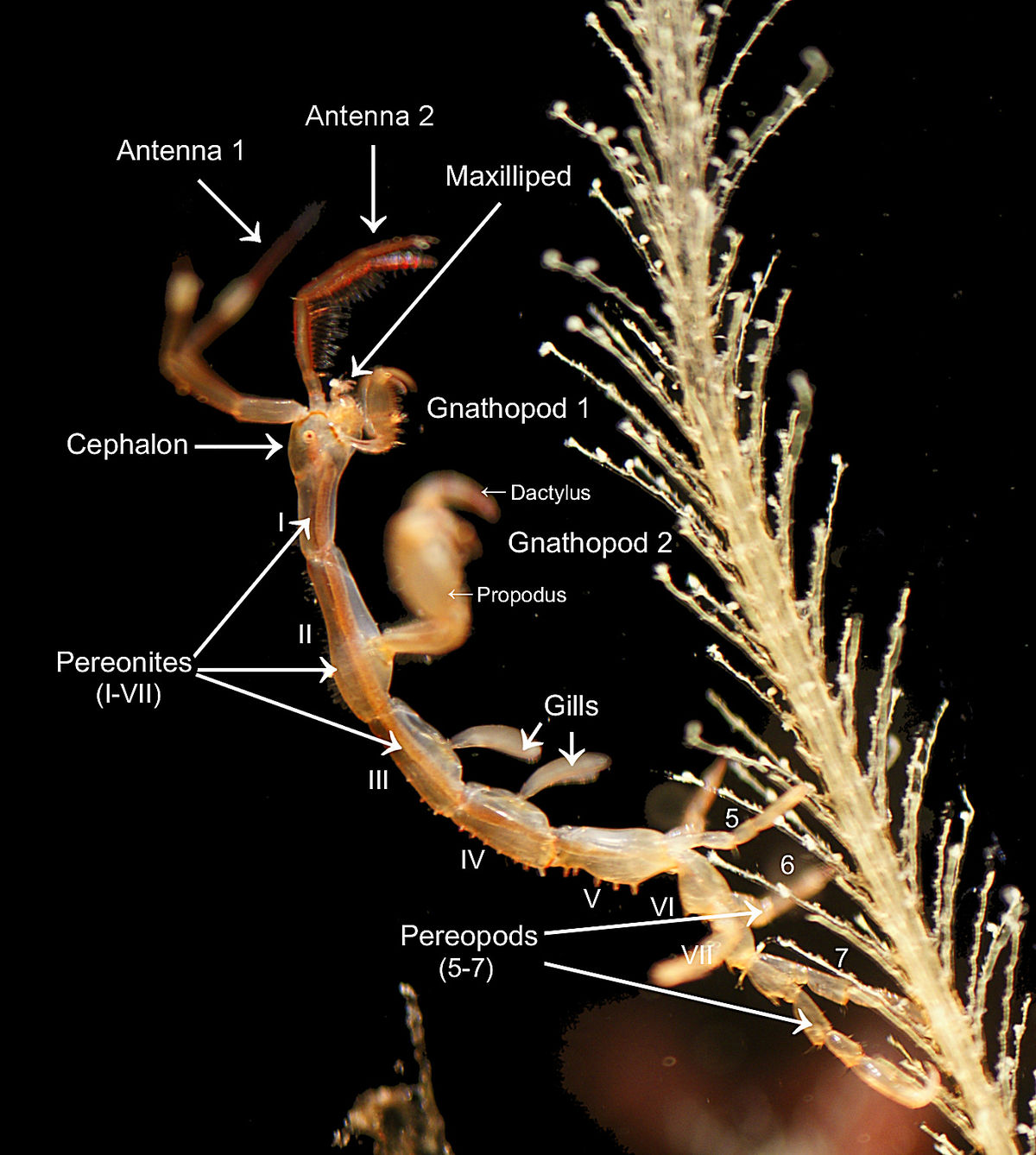

The next step is morphology. I don’t know about you, but when I hear the word “morphology”, I think of this:

It seems a bit like a scary and jingoistic word meant for the likes of biologists with Ph.Ds, but all morphology really means is how to build a word. But Tabby, you say, I thought I already created words. I have a whole list right here!

Yes, you did create some words, root words. However, the next step is add some complexity to those words. How will you put together sounds and words to change their meaning based on how you need to use the root word?

Dissecting Morphology (See what I did there?)

So… How does a root transform into a word? This site has a great explanation for how it all works. Check it out to get a basic understanding of the concept, if you are interested.

Words are made of pieces–the root and whatever sounds are affixed to them to create meaning. For example, dogs is made up of dog and -s. Together they mean “more than one dog.”

In Korvet, that is achieved by adding -ei to the end of a root.

Yasjer (dog) + -ei (plural marker) = yasjerei (multiple dogs)

Both dogs and yasjerei are made up of two morphemes–the root for “dog” and the plural marker. In this case, dog and yasjer are free morphemes because they have meaning on their own. The plural markers -s and –ei require something attached in order to mean anything, making them bound morphemes.

For you more visual learners, another way to look at it is like this:

This is a morphology tree for the word “independently”. You can see different morphemes come together to build the entire word, such as the root “depend” and -ly to make it an adverb. “Depend” is a free morpheme because it has meaning on its own, whereas -ly is a bound morpheme, needing to be attached to a verb, adjective, or adverb in order to have meaning.

Inflections

The examples -ei, -s, and -ly above are inflections, or affixes attached to words to adjust their meaning. Some other examples are -ed to make a verb past tense, -est to make adjective a superlative, or un- to indicate the negation/reversal of a verb. Some more inflections in Korvet are adding -m to a noun to make it the object of sentence.

Se (I) + -m [object]= sem (me)

There are several types of languages when it comes to inflections:

Agglutinative – each affix has a fixed meaning (Tagalog, Turkish, Hungarian, Japanese).

Fusional – an affix may have more than one meaning (Spanish, Pashto, German, Irish)

Isolating – there are no affixes, and meanings are modified by using additional words (Mandarin, Yoruba).

Polysynthetic – nouns and other sentence parts are embedded in verbs and often come out as “sentence-words” (Nahuatl, Mohawk, Tiwi).

For most natural languages, they have elements of different types of inflection strategies.

Korvet is overall an agglutinative language–each affix has a fixed meaning. It’s pretty straight forward in that regard for simplicity’s sake–each part of speech has its own affix.

Inflections can come in the form of suffixes: -ed, -ing, and -s to indicate verb tense in English. There are also prefixes: pre-, un-, or dis-. There are even infixes, which are inserted into a root. English doesn’t have any true infixes that I know of, but something that comes close is when someone says, “Abso-fricking-lutely!”

Korvet has all three. To create an adjective, add an a- to the beginning:

a- + sjeret (beauty) = asjeret (beautiful)

To indicate being behind or after something, add -toa:

bret (tree) + –toa (behind) = brettoa (behind the tree)

To indicate being in a multiple of something, add -ei, then -ti:

jen (house) + –ei (plural) + –ti (in) = jeneiti (in the houses)

Putting It All Together

Again, now it is your turn. How do you organize all these morphemes?

Once you decide what kind of morphological structure (i.e. agglutinative, isolating, etc.) your language will follow, write down some affixes and their meaning. You could organize it by parts of speech (noun, verb, adjective, etc.), or you could separate by prefix, suffix, and infix.

If you’ve been brave enough to try out Polyglot, that probably has some good ways to organize all the morphemes you’ve created.

This will tie into the next step, which is figuring out the syntax of your language, so keep that in mind! For now, it might be best to just keep notes. Next time, I will lay out the basics of creating a syntax, or grammar structure, for your conlang.

Happy conlanging!